I’ve been using this service for a couple of days now, and it’s made my internet access so much faster. That alone is a plus, and I never thought there would be a contender for Cloudflare in this area.

Changing Passwords Regularly Actually Weakens Security

-

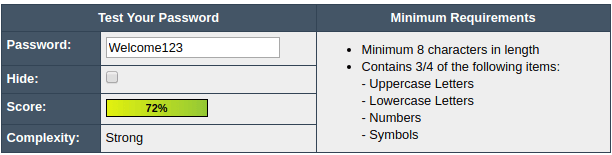

The recent high profile breaches impacting organisations large and small are a testament to the fact that no matter how you secure credentials, they will always be subject to exploit. Can a password alone ever be enough ? in my view, it’s never enough. The enforced minimum should be at least with a secondary factor. Regardless of how “secure” you consider your password to be, it really isn’t in most cases – it just “complies” with the requirement being enforced.Here’s classic example. We take the common password of “Welcome123” and put it into a password strength checker

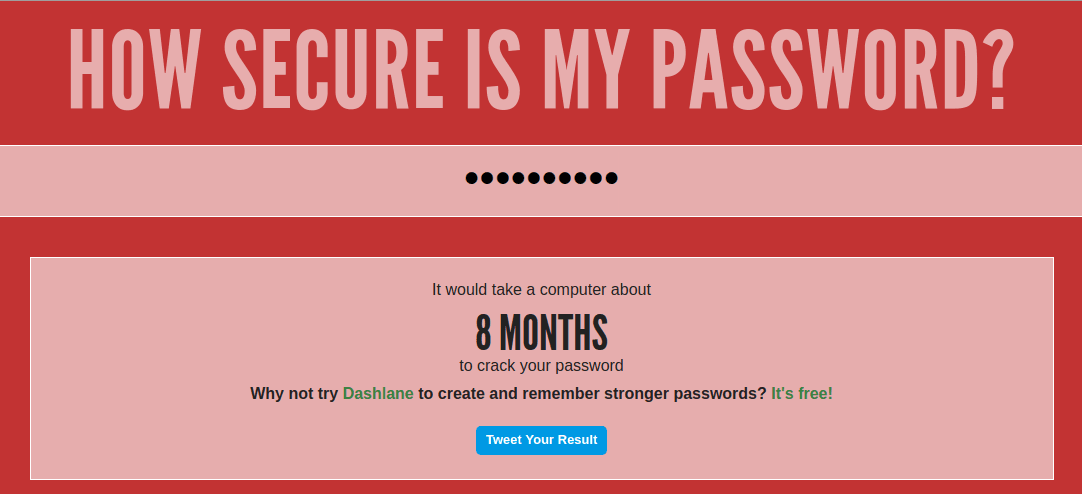

According to the above, it’s “strong”. Actually, it isn’t. It’s only considered this way because it meets the complexity requirements, with 1 uppercase letter, at least 8 characters, and numbers. What’s also interesting is that a tool sponsored by Dashlane considers the same password as acceptable, taking supposedly 8 months to break

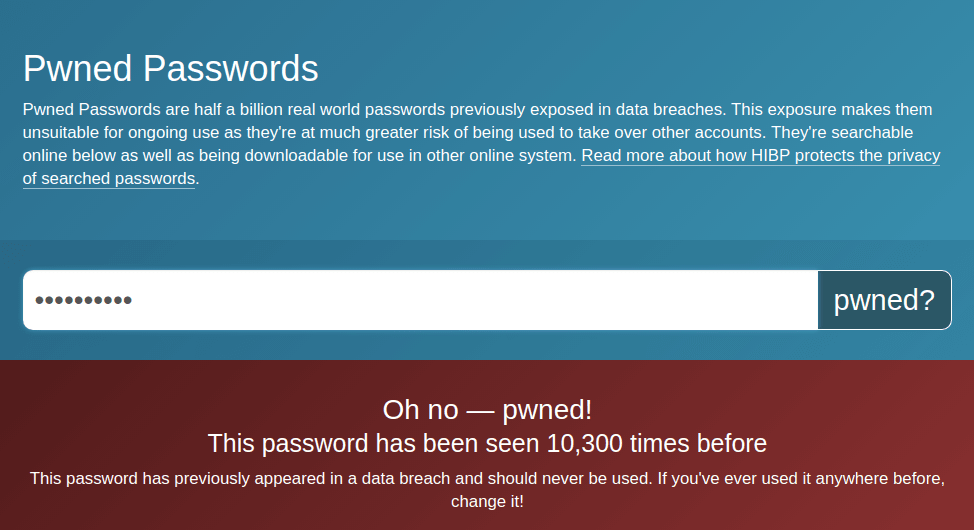

How accurate is this ? Not accurate at all. The password of “Welcome123” is in fact one of the passwords contained in any penetration tester’s toolkit – and, by definition, also used by cyber criminals. As most of this password combination is in fact made up of a dictionary word, plus sequential numbers, it would take less than a second to break this rather than the 8 months reported above. Need further evidence of this ? Have a look at haveibeenpwned, which will provide you with a mechanism to test just how many times “Welcome123” has appeared in data breaches

Why are credentials so weak ?

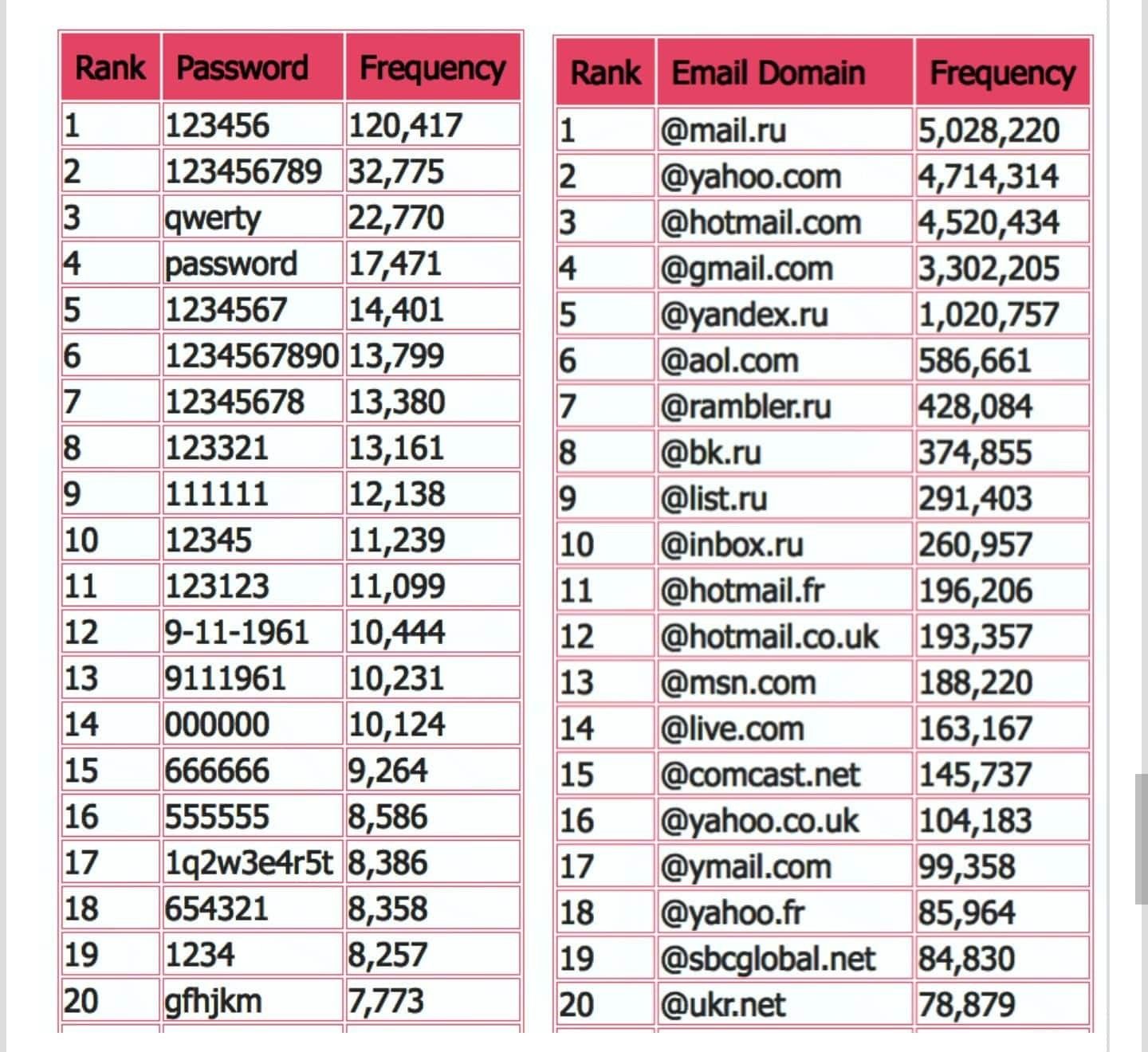

My immediate response to this is that for as long as humans have habits, and create scenarios that enable them to easily remember their credentials, then this weakness will always exist. If you look at a sample taken from the LinkedIn breach, those passwords that occupy the top slots are arguably the least secure, but the easiest to remember from the human perspective. Passwords such as “password” and “123456” may be easy for users to remember, but on the flip side, weak credentials like this can be broken by a simple dictionary attack in less than a second.

Here’s a selection of passwords still in use today – hopefully, yours isn’t on there

We as humans are relatively simplistic when it comes to credentials and associated security methods. Most users who do not work in the security industry have little understanding, desire to understand, or patience, and will naturally choose the route that makes their life easier. After all, technology is supposed to increase productivity, and make tasks easier to perform, right ? Right. And it’s this exact vulnerability that a cyber criminal will exploit to it’s full potential.Striking a balance between the security of credentials and ease of recall has always had it’s challenges. A classic example is that networks, websites and applications nowadays typically have password policies in place that only permit the use of a so-called strong password. Given the consolidation and overall assortment of letters, numbers, non-alphanumeric characters, uppercase and lowercase, the password itself is probably “secure” to an acceptable extent, although the method of storing the credentials isn’t. A shining example of this is the culture of writing down sensitive information such as credentials. I’ve worked in some organisations where users have actually attached their password to their monitor. Anyone looking for easy access into a computer network is onto an immediate winner here, and unauthorised access or a full blown breach could occur within an alarmingly short period of time.

Leaked credentials and attacks from within

You could argue that you would need access to the computer itself first, but in several historical breach scenarios, the attack originated from within. In this case, it may not be an active employee, but someone who has access to the area where that particular machine is located. Any potential criminal has the credentials – well, the password itself, but what about the username ? This is where a variety of techniques can be used in terms of username discovery – in fact, most of them being non-technical – and worryingly simple to execute. Think about what is usually on a desk in an office. The most obvious place to look for the username would be on the PC itself. If the user had recently logged out, or locked their workstation, then on a windows network, that would give you the username unless a group policy was in place. Failing that, most modern desk phones display the name of the user. On Cisco devices, under Extension Mobility, is the ID of the user. It doesn’t take long to find this. Finally there’s the humble business card. A potential criminal can look at the email address format, remove the domain suffix, and potentially predict the username. Most companies tend to leverage the username in email addresses mainly thanks to SMTP template address policies – certainly true in on premise Exchange environments or Office 365 tenants.

The credentials are now paired. The password has been retrieved in clear text, and by using a simple discovery technique, the username has also been acquired. Sometimes, a criminal can get extremely lucky and be able to acquire credentials with minimal effort. Users have a habit of writing down things they cannot recall easily, and in some cases, the required information is relatively easily divulged without too much effort on the part of the criminal. Sounds absurd and far fetched, doesn’t it ? Get into your office early, or work late one evening, and take a walk around the desks. You’ll be unpleasantly surprised at what you will find. Amongst the plethora of personal effects such as used gym towels and footwear, I guarantee that you will find information that could be of significant use to a criminal – not necessarily readily available in the form of credentials, but sufficient information to create a mechanism for extraction via an alternative source. But who would be able to use such information ?

Think about this for a moment. You generally come into a clean office in the mornings, so cleaners have access to your office space. I’m not accusing anyone of anything unscrupulous or illegal here, but you do need to be realistic. This is the 21st century, and as a result, it is a security measure you need to factor in and adopt into your overall cyber security policy and strategy. Far too much focus is placed on securing the perimeter network, and not enough on the threat that lies within. A criminal could get a job as a cleaner at a company, and spend time collecting intelligence in terms of what could be a vulnerability waiting to be exploited. Another example of “instant intelligence” is the network topology map. Some of us are not blessed with huge screens, and need to make do with one ancient 19″ or perhaps two. As topology maps can be quite complex, it’s advantageous to be able to print these in A3 format to make it easier to digest. You may also need to print copies of this same document for meetings. The problem here is what you do with that copy once you have finished with it ?

How do we address the issue ? Is there sufficient awareness ?

Yes, there is. Disposing of it in the usual fashion isn’t the answer, as it can easily be recovered. The information contained in most topology maps is often extensive, and is like a goldmine to a criminal looking for intelligence about your network layout. Anything like this is classified information, and should be shredded at the earliest opportunity. Perhaps one of the worst offences I’ve ever personally experienced is a member of the IT team opening a password file, then walking away from their desk without locking their workstation. To prove a point about how easily credentials can be inadvertently leaked, I took a photo with a smartphone, then showed the offender what I’d managed to capture a few days later. Slightly embarrassed didn’t go anywhere near covering it.

I’ve been an advocate of securing credentials for some time, and recently read about the author of “NIST Special Publication 800-63” (Bill Burr). Now retired, he has openly admitted the advice he originally provided as in fact, incorrect

“Much of what I did I now regret.” said Mr Burr, who advised people to change their password every 90 days and use obscure characters.

“It just drives people bananas and they don’t pick good passwords no matter what you do.”

The overall security of credentials and passwords

However, bearing in mind that this supposed “advice” has long been the accepted norm in terms of password securuty, let’s look at the accepted standards from a well-known auditing firm

It would seem that the Sarbanes Oxley 404 act dictates that regular changes of credentials are mandatory, and part of the overarching controls. Any organisation that is regulated by the SEC (for example) would be covered and within scope by this statement, and so the argument for not regularly changing your password becomes “invalid” by the act definition and narrative. My overall point here is that the clearly obvious bad password advice in the case of the financial services industry is negated by a severely outdated set of controls that require you to enforce a password change cycle and be in compliance with it. In addition, there are a vast number of sites and services that force password changes on a regular basis, and really do not care about what is known to be extensive research on password generation.

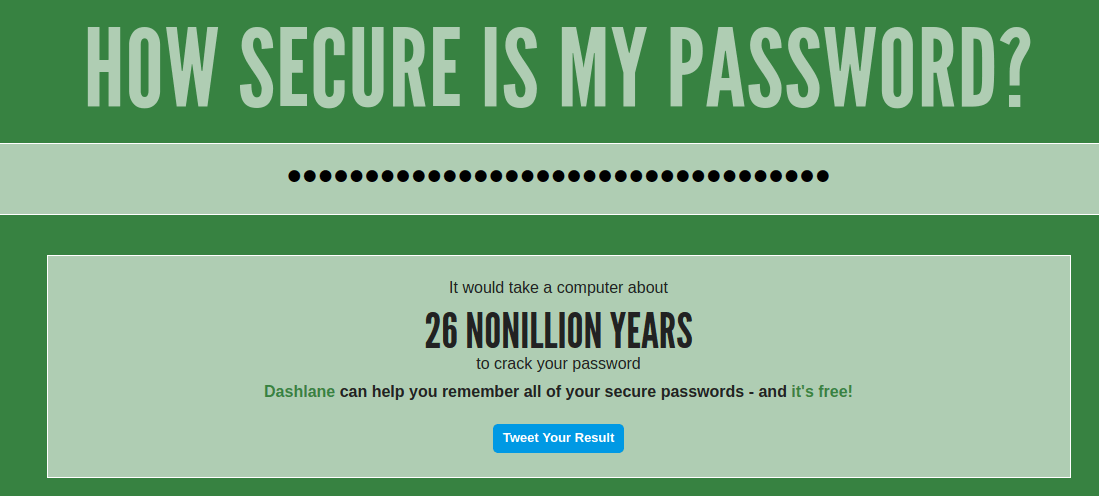

The argument for password security to be weakened by having to change it on a frequent basis is an interesting one that definitely deserves intense discussion and real-world examples, but if your password really is strong (as I mentioned previously, there are variations of this which are really not secure at all, yet are considered strong because they meet a complexity requirement), then a simple mutation of it could render it vulnerable. I took a simple lowercase phrase

mypasswordissimpleandnotsecureatall

The actual testing tool can be found here. So, does a potential criminal have 26 nonillion years to spare ? Any cyber criminal who possesses only basic skills won’t need a fraction of that time as this password is in fact made up of simple dictionary words, is all lowercase, and could in fact be broken in seconds.My opinion ? Call it how you like – the password is here to stay for the near future at least. The overall strength of the password or credentials stored using MD5, bCrypt, SHA1 and so on are irrelevant when an attacker can use established and proven techniques such as social engineering to obtain your password. Furthermore, the addition of 2FA or a SALT dramatically increases password security – as does the amount of unsuccessful attempts permitted before the associated account is locked. This is a topic that interests me a great deal. I’d love to hear your feedback and comments.

-

undefined phenomlab referenced this topic on

undefined phenomlab referenced this topic on